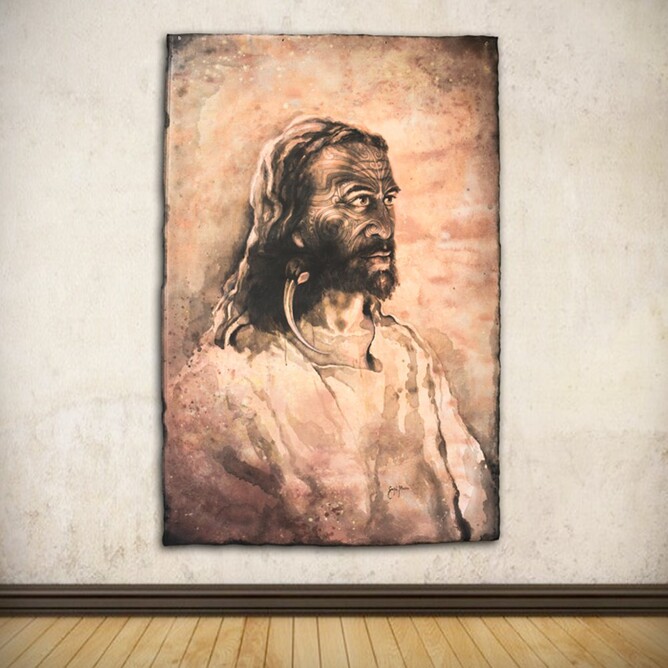

“Maori Jesus” is Sofia Minson's depiction of the Messiah as tangata whenua (indigenous Maori) with full-face moko (traditional tattoo). A celebration and revival of Maori portrait painting.

'Maori Jesus' by Sofia Minson, acrylic and flashe on loose canvas, 1480 x 970mm, 2014

You have until 19 April 2014 to see the work for yourself at Bryce Gallery in Christchurch in an exhibition called "Somebody" - a people focussed exhibition with 14 artists and 32 paintings.

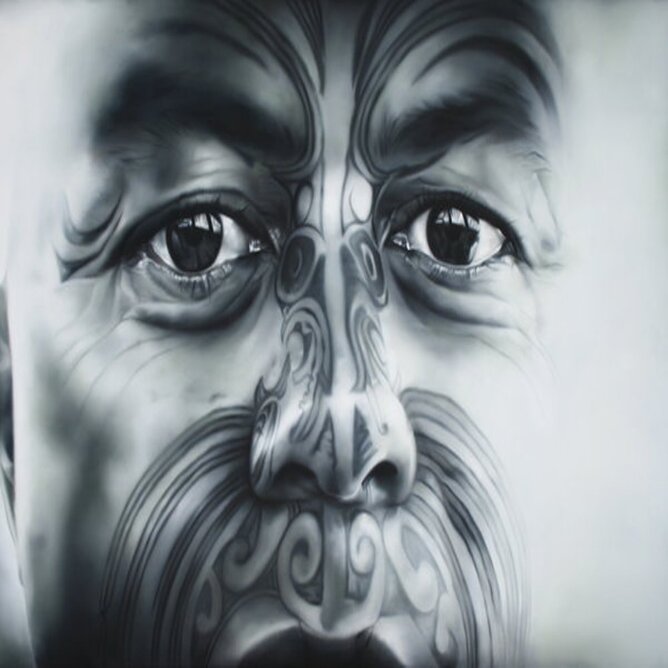

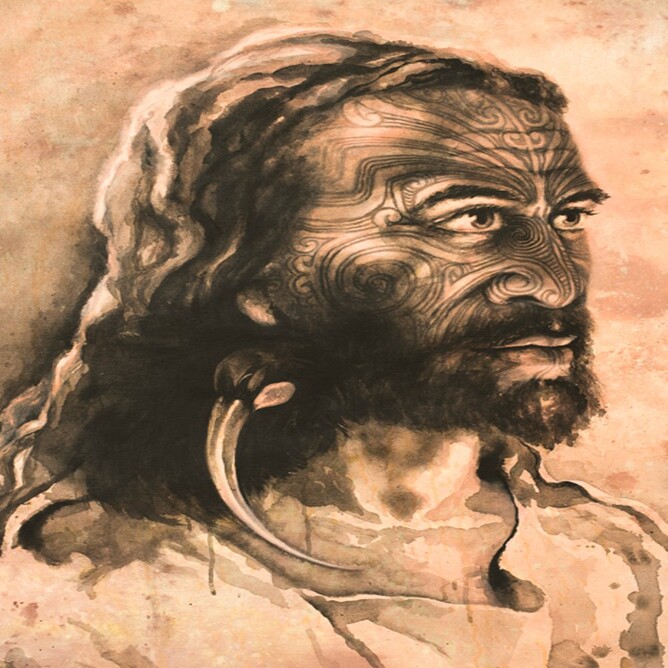

Close-up of 'Tukukino' by Gottfried Lindauer, oil on canvas, 1878. Minson has painted 'Maori Jesus' with an extinct native huia bird tucked into his neck, in the vein of C.F. Goldie and Gottfried Lindauer’s 19th century portraits of Maori.

This Easter, traditionally a time of rebirth, fertility, the resurrection of Christ and Springtime, Minson celebrates a revival in the the art of Maori portrait painting, which has arguably been in limbo since the likes of Goldie and Lindauer. While Minson is inspired by their works, she says her Maori portraits “are far from Goldie’s recordings of a vanishing race” and are intended to fill an important niche for her generation. Nowadays we find that it is not so easy to define who or what is Maori. As a Maori artist of mixed heritage (Ngati Porou, Swedish, English and Irish) she uses traditional Western figurative painting to show the living, evolving and diverse culture of Maori in the 21st century.

Minson says her personal goal with this portrait "is to sense the fluidity and exchange of faith, wairua (spirit), culture, art and religion between people through the ages."

Her representation of Christ as ethnically Maori may provoke questions about cultural appropriation by religion, a widely-talked-about example being early Christianity, which developed in an era of the Roman Empire, adopting European Pagan symbols and rituals in order to replace diverse beliefs and practices with the new religion.

'Turumakina' by Sofia Minson, 2010, oil on canvas, 1400 x 2100mm

It may also call into question the line between ‘sacred’ and ‘profane’ both in terms of Christianity and Maori tradition. Take for example the practice of Ta Moko Kanohi (facial tattooing), which with its mark carries deep ancestral ties. Is it profane for Jesus to wear a moko in this picture, or is it sacred? Is it profane to see moko drawn on the faces of Maori cultural performers, or does kapa haka and other creative pursuits have the sacred role of carrying the culture and ties to our ancestors forward into a new generation?

When creating this work, Minson was also interested in James K. Baxter (1926 - 1972) and his poem “The Maori Jesus.” Baxter was one of the first Pakeha to respect the mana (honour) of Maori, who he insisted should be treated as the ‘elder brother’ in terms of spirituality and wisdom. A section of the poem goes as follows:

“The Maori Jesus said, 'Man,

From now on the sun will shine.'

He did no miracles;

He played the guitar sitting on the ground.

The first day he was arrested

For having no lawful means of support.

The second day he was beaten up by the cops

For telling a dee his house was not in order.

The third day he was charged with being a Maori

And given a month in Mt Crawford.

The fourth day he was sent to Porirua

For telling a screw the sun would stop rising.

The fifth day lasted seven years

While he worked in the Asylum laundry

Never out of the steam.

The sixth day he told the head doctor,

'I am the Light in the Void;

I am who I am.'

The seventh day he was lobotomised;

The brain of God was cut in half.”

- James K. Baxter

With Easter's focus on rebirth, let's consider that for a culture to survive and for its people to flourish, it must constantly re-make itself and become a blend of old and new. Maori culture has been doing this since the Maori renaissance of the 1970s and the revival of te reo (the Maori language). For a religion such as Christianity to flourish it naturally does the same thing, it blends old doctrine with new culture and sometimes even the face of its new devotees.

In a December 2013 Huffington Post article by Jesse Washington entitled “The Race Of Jesus Is Unknown Yet Powerful”, the matter of the racial portrayal of Jesus throughout history is discussed:

Close-up of Minson's 'Maori Jesus'

For two thousand years, he has been worshipped and adored. Multitudes look to him each day. And yet nobody really knows the face of Jesus. That has not stopped humanity's imagination, or its yearning to draw Jesus as close as possible.

Why should we even care what Jesus looked like? If his message is God and love, isn't his race irrelevant? Some say God wanted it that way, since there are no references to Jesus' earthly appearance in the Bible.

Jesus can be safely categorized as a Jew, born about 2,000 years ago in the Middle East in what is now Palestinian territory. Therefore, many scholars believe that Jesus must have looked "Arab," with brownish skin.

"Today, in our categories, we would probably think of him as a person of color," said Doug Jacobsen, a professor of church history and theology at Messiah College.

If this is so obvious, though, why does a Google image search for "Jesus" reveal countless pictures of a European man with straight hair, fair skin and, often, blue eyes? Why is that the prevalent image in America, from stained glass windows to movies to children's books?

The first pictures of Jesus appeared several hundred years after his death, said Edward Blum, co-author of "The Color of Christ: The Son of God and the Saga of Race in America." Some depicted him in animal form, as a lion or a lamb. Blum said that from about 700 to 1500 A.D., various Jesus images proliferated throughout Europe, the Middle East and northern Africa — including hosts of black Jesus pictures.

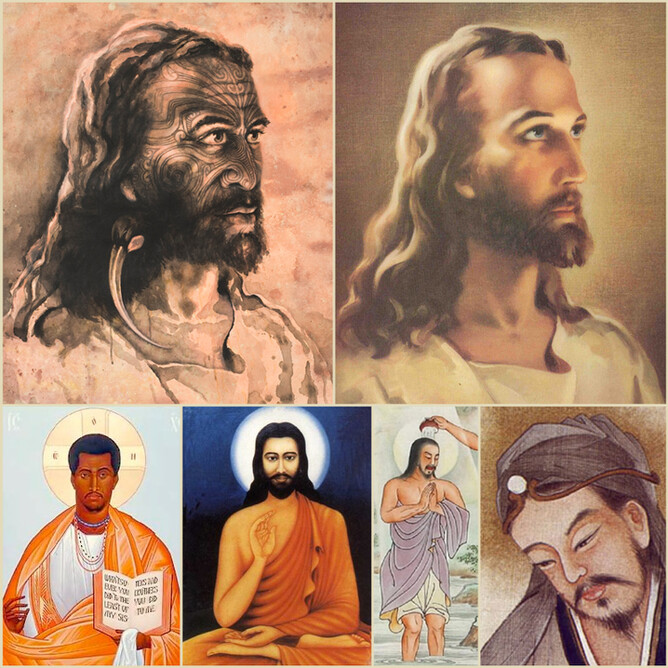

"People in every culture portray Jesus looking like people they knew," said Doug Jacobsen, a professor of church history and theology at Messiah College. "They depict him as one of their own."

Dillaman, the pastor, has a book that offers Bible images from different world cultures — a last supper where everyone is Thai; images of Jesus as Chinese or African. "All these ethnicities are trying to capture Jesus in their own skin, if you will," he said.

The many faces of Jesus represented by artists of different cultures and ethnicities

By the 1500s, Blum said, 90 percent of Christians were European. As Europe colonized the globe, they took white Jesus with them.

In America, white Jesus images started to become widespread in the early 1800s, according to Blum, coinciding with a dramatic rise in the number of slaves, a push to move Native Americans further west, and a growing manufacturing capability.

Today, a white Jesus image is ingrained in American culture. "When we live in a world with a billion images of white Jesus, we can say he wasn't white all we want, but the individual facts of our world say something different," Blum said.

"Jesus is white without words. It's at the assumption level," Blum said. "Lodged deep down inside is this assumption that Jesus was a white man."

There also is a desire to fit Jesus into modern racial classifications. In America today, this logic goes, Jews are white. Jesus was a Jew, so Jesus must be white.

Yet Jews did not originate in Europe, and for centuries were considered to belong to a non-white race of their own. Only recently have they been moved into America's "white" column, along with Irish and Italians.

"The categories of white and black, coming out of the American experience, it just doesn't make a lot of sense to apply them to Jesus," said Joseph Curran, an associate professor of religion at Misericordia University.

"The best inference is what part of the world he was from — he looked like a Palestinian because he was from that part of the world," Curran said. "Does that mean he was black or white? I don't think those categories matter much."

For Carol Swain, a scholar of race at Vanderbilt University and a "Bible-believing follower of Jesus Christ," the whole debate is totally irrelevant.

"Whether he's white, black, Hispanic, whatever you want to call him, what's important is that people find meaning in his life," Swain said.

"As Christians we believe that he died on the cross for the redemption of our sins," she said. "To me that's the only part of the story that matters — not what skin color he was."

- Jesse Washington covers race and ethnicity for The Associated Press.

Bryce Gallery in Christchurch is exhibiting 'Maori Jesus' until 19 April 2014 in an exhibition called "Somebody" - a people focussed exhibition with 14 artists and 32 paintings. Featuring works from Clark Esplin, Geoff Williams, Hamish Allan, Jacky Pearson, JK Reed, Julia Drake, Ken Hunt, Mark Olsen, Mark Zhu, Min Kim, Sang Kyu Moon, Simon Williams, Sofia Minson, Stephanie McEwin, Svetlana Orinko.

Bryce Gallery: Corner Riccarton Rd and Paeroa St, Riccarton, Christchurch.

Open 7 days: 10am – 5pm (Mon – Fri), 10am – 4pm (Sat), 11am – 4pm (Sun).

Phone: +64 3 348 0064. Email: art2die4@brycegallery.co.nz.

The Limited Edition Print of 'Maori Jesus' by Sofia Minson is an edition of 75 signed prints available on matte paper of museum archival quality called hahnemuhle photo rag 308gsm. Image size is 550mm high x 458mm wide surrounded by an unprinted white border. Shipping is FREE within NZ and $35 everywhere else (prices are NZD). Unframed print arrives sealed in protective tube or sleeve. Click here to contact us if you have questions.

Posted by artist Sofia Minson from NewZealandArtwork.com

New Zealand Maori portrait and landscape oil paintings